Elbow

Fragmented Medial Coronoid Process

Osteochondritis dissecans - Medial aspect of humeral condyle

Ununited Anconeal Process

Ununited medial humeral epicondyle

Elbow luxation

Trauma/fractures

Fragmented Medial Coronoid Process

History and Signalment

Breeds - Primarily affects large and giant breeds of dogs, such as Labrador retrievers, Newfoundlands, Bernese Mountain dogs, Rottweilers, etc.

Gender - Males are affected about twice as frequently as females.

Age - Clinical signs begin between 5 to 8 months of age. In some dogs, a problem is not suspected and lameness may not become apparent until middle age or even later. By this time, there is often end-stage arthritis, with complete loss of cartilage. Therefore, careful evaluation at approximately 6 to 8 months of age is critical.

Etiology - There is a heritable component of the disease, so screening of breeding pairs is recommended. Environmental factors the contribute to the development include excessive weight and rapid growth rate.

Clinical Findings

Lameness, swelling of the elbow joint, swinging out of the forelimb to avoid flexing the elbow joint, and short, choppy strides. Approximately 80% of the time, both elbows are affected, therefore asymmetry of gait may not be apparent because both forelimbs are equally affected. The elbow joint should be put through a range of motion. Any loss of range of motion of the elbow is associated with osteoarthritis and lameness. Palpation of the elbow joint may reveal swelling or effusion of the elbow joint. Sometimes this is subtle, so palpating both elbows simultaneously in a standing position may allow appreciation of very mild changes. Palpating the area of the medial coronoid process while the elbow joint is supinated and pronated may demonstrate pain.

Diagnostics

Lateral, flexed lateral, AP, and sometimes oblique radiographs of the elbow aid in the diagnosis. Blunting of the medial coronoid process, occasional observation of the fragment itself, and secondary arthritic changes, including sclerosis of the trochlear notch, osteophytes on the anconeal process, radial head, ulna in the coronoid region, and distal humerus, are suggestive of a fragmented medial coronoid process. The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) and the Elbow Working Group in Europe provide assessment of radiographs to screen for elbow conditions.

CT of the elbows have greatly increased the sensitivity of fragmented medial coronoid process diagnosis. Cross-sectional and sagittal views demonstrate the fragment and secondary osteoarthritis.

Treatment Options

Unfortunately, no treatment has been demonstrated to be effective in halting the progression of osteoarthritis. In general, the earlier treatment is initiated, the more likely the patient will respond. Many surgical options exist, including removal of the fragment with arthroscopy or arthrotomy, subtotal coronoidectomy, microfracture of subchondral bone, osteotomy of the proximal ulna, biplanar oblique dynamic proximal ulnar osteotomy, proximal ulnar osteotomy (PAUL), sliding humeral osteotomy (SHO), biceps ulnar release procedure (BURP), canine unicompartmental elbow (CUE), and total elbow replacement. The choice of surgical technique is somewhat controversial and depends on the experience and comfort level of the surgeon. Evaluation of any contributing causes of the fragmented medial coronoid process, such as elbow incongruity and severity of osteoarthritis should be considered in the selection of surgical technique.

Medical management should be instituted in all cases following surgery, and may be the primary initial treatment in some situations. Additional information regarding management of osteoarthritis may be found in the arthritis section.

Osteochondritis dissecans - Medial aspect of humeral condyle

Signalment

Breeds – Large and giant breed dogs

Gender – Males are predisposed, but females also affected

Age – Generally noted from 4 to 9 months of age

Etiology - Abnormal endochondral ossification of the deep layers of articular cartilage results in focal areas of thickened cartilage that are prone to injury. In the absence of excessive stress, the lesion may heal. However, further stress on the cartilage may result in a cartilage flap. This condition is termed osteochondritis dissecans (OCD).

History

Mild to moderate lameness, decreased activity

Clinical Findings

Mild to moderate lameness, atrophy of the forelimb muscles, pain may be elicited with hyperextension of the elbow and palpation over the medial compartment of the elbow

Diagnostics

Generally diagnosis suspected on orthopedic exam and confirmed with an AP radiograph of the elbow. CT evaluation is very helpful in diagnosing OCD also.

Treatment Options

Removal of cartilage flap with an arthrotomy or arthroscopy, curettage of subchondral bone, change diet to a large breed growth diet, nonsterodal anti-inflammatory medication, rehabilitation

Ununited Anconeal Process

Signalment

Breeds – most common in German shepherd dogs, and also Bassett hounds and Saint Bernards

Gender – Males may be predisposed

Age – Diagnosed after 5 1/2 months of age

Etiology - The anconeal process has a physis which normally closes at 5 months of age. If it remains open at 6 months of age, it is generally a pathologic condition and will not close without intervention. Some believe that UAP is a manifestation of OCD, with failure of endochondral ossification. Others believe there may be flattening of the semilunar notch or incongruent growth with the radial head pushing up on the anconeal process and preventing fusion.

History

Affected dogs have a history of lameness that begins between 5 and 6 months of age. Additionally, dogs may be less active compared to littermates.

Clinical Findings

Dogs are usually presented with a weight-bearing lameness of the affected limb between 5 and 6 months of age. Typically, there is moderate to severe effusion of the caudolateral compartment of the elbow, with restricted range of motion. Dogs may stand with the antebrachium externally rotated, and may have a swinging limb lameness with limited motion of the elbow joint. Dogs may have decreased range of motion if osteoarthritis is already present. Some dogs may not be identified with lameness until they are several years old.

Diagnostics

A lateral radiograph with the elbow in a flexed position confirms the diagnosis. A radiolucent line is present at the junction of the anconeal process and the ulna. Arthritic changes usually progress rapidly young dogs.

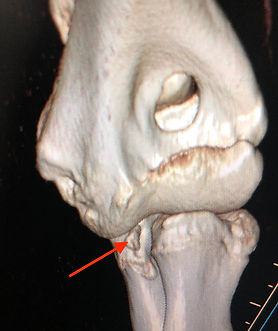

Ununited anoconeal process. The arrow indicates the radiolucent line indicating the site of the UAP

Ununited medial humeral epicondyle (calcification of the flexor tendons of the medial epicondyle)

History and Signalment

Breeds – Labrador retrievers seem to be predisposed, along with German Shepherd dogs and English setters.

Gender – Males may be predisposed

Age – Usually evident by 5-6 months of age, but some are asymptomatic and may go unrecognized or recognized at any older age.

Etiology - The cause is unknown. There may be an association with a traumatic event. In many cases, there has been no apparent trauma and a form of osteochondrosis has been suggested

Clinical Findings

Lameness may be present. There is usually marked swelling in the region of the medial epicondyle of the humerus, and there may be pain on direct palpation. The condition is often bilateral.

Diagnostics

Flexed lateral and A-P radiographs are evaluated for bone densities at or distal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus. Careful evaluation of radiographs and orthopedic evaluation are important to be certain that elbow dysplasia, especially fragmented medial coronoid process, is not present.

Treatment Options

Treatment is generally removal of all bony fragments if the dog is lame. Careful dissection is needed to avoid damaging tendons and muscles. I have reduced a large fragment and compressed it with a screw in one case, but fragments are usually not large enough or thick enough to do this.

Elbow luxation

Signalment

Breeds – Any breed is susceptible, but larger breeds are most frequently affected

Gender – No predilection

Age – Any age

Etiology - Trauma. Many cases occur as a result of automobile trauma. Because of this and the fact that the forelimb is affected, careful evaluation of the thoracic structures is important to detect cardiac arrhythmias, pneumothorax, pulmonary edema, or diaphragmatic hernia. Although congenital elbow luxation occurs, especially in chondrodystrophic breeds, this discussion will center on traumatic elbow luxation.

History

There is an acute onset of severe lameness as a result of trauma. Caution should be taken to assess the entire patient for other injuries.

Clinical Findings

Dogs are usually nonweight-bearing lame. Lateral luxation is by far the most common. The antebrachium and foot are abducted and the elbow is held in a flexed position. There is pain and crepitus with manipulation, and the radial head is quite prominent and located lateral to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus compared to the contralateral side.

Diagnostics

Radiographs confirm the clinical diagnosis. Radiographs often also show bone fragments associated with the damaged collateral ligament.

Treatment Options

Significant effort should be made to attempt closed reduction, which may carry a more favorable prognosis. The animal should be anesthetized when safe to do so, and traction should be applied by hanging the limb (the body should be lifted from the table) from a ceiling hook or IV pole for 5-10 minutes to fatigue the muscles. If the anconeal process is still within the supracondylar foramen, strong digital pressure applied to the radial head may reduce the luxation with the animal in a distracted position. If this is not successful, the elbow joint is flexed to approximately 100 degrees, distracted as best possible, then the elbow is internally rotated while applying firm digital pressure to the radial head and abducting the elbow. If successful, there is a distinct feel as the reduction occurs. There may be some crepitus felt during the reduction. Radiographs should be made post-reduction to be certain that the elbow has been completely reduced. It is quite common to think that the elbow has been reduced, only to find that it was only partially reduced. Additional attempts may be tried. If reduction is successful, the elbow is usually maintained in an extended weight bearing position in a spica splint for 2 weeks. If attempts of closed reduction are unsuccessful, then open reduction and repair of the damaged collateral ligaments with suture techniques, prosthetic collateral repair, or tissue anchors is generally recommended.

Trauma/fractures

Signalment

Breeds – Any breed

Gender – No gender predilection

Age – Any age, although skeletally immature dogs are prone to fractures of the lateral aspect of the humeral condyle.

Etiology – Trauma. Many cases occur as a result of jumping down from a distance or landing awkwardly. Other cases occur as a result of automobile trauma. If the fracture is a result of severe trauma, careful evaluation of the thoracic structures is important to detect cardiac arrhythmias, pneumothorax, pulmonary edema, or diaphragmatic hernia. If minimal trauma results in a fracture, consideration should be made to incomplete ossification of the humeral condyle, especially common in spaniel breeds. The contralateral side should also be evaluated because the condition may occur bilaterally.

History

Often owners witness trauma, such as a fall, hit by automobile, or other sudden traumatic event that results in sudden onset of severe lameness.

Clinical Findings

Fractures of the distal humerus/elbow result in pain on manipulation and crepitation during manipulation of the elbow. Palpable anatomical differences are usually apparent.

Diagnostics

Radiographs are generally diagnostic, but careful evaluation should be made to distinguish fractures of the lateral or medial aspects of the humeral condyle from bicondylar (Y or T) fractures of the distal humerus. CT evaluation may give additional details.

Treatment Options

Fractures of the humeral condyles require internal fixation to restore anatomy and function. Fractures of the lateral (more common) or medial aspects of the humeral condyle are generally repaired with the a transcondylar screw placed in lag fashion with additional fixation of the epicondyle to the mainshaft of the humerus, with either an antirotational pin or K wire, or a bone plate and screws.

Bicondylar (T or Y) fractures of the humerus are more serious. In some cases, an olecranon osteotomy may be necessary to gain better access to the humeral condyle for reduction and fixation, especially if the fracture is older than 5 days. This requires fixation of the osteotomy with a pin and tension band after the main repair is performed. This situation results in more soft tissue damage and subsequent fibrous tissue formation, necessitating excellent post-operative rehabilitation to achieve as normal function of the elbow as possible. If possible, a better option is to use separate approaches to the medial and lateral aspects of the joint. A transcondylar screw is placed in lag fashion after the articular surface is anatomically reduced. The medial aspect of the condyle is attached to the mainshaft of the humerus with a bone plate and screws. The lateral aspect of the condyle is attached to the mainshaft of the humerus with either an intramedullary pin or bone plate and screws.

Treatment Options

The traditional treatment is removal of the UAP. Recently, other surgical approaches have included lag screw fixation of the UAP with the main segment of the anoconeal process. Another treatment which is sometimes used separately or in combination with screw fixation is an ostectomy of the proximal ulna, in hopes that any incongruity will be relieved and allow the UAP to successfully fuse. If the condition is chronic, the fragment edges do not match well because of the erosion of bone and cartilage, and the piece may not be easily fixed in place. Also, because there may be a defect in endochondral ossification, healing may be delayed. With any treatment, OA progresses and further treatment revolves around management of the pain and OA.